![]()

In September of 1953, John Atkin designed Maid of Endor for a Mr Harry Meyer. She was, he said, "based on much larger fishing vessels from the Vendee area of Brittany that were long proven for their seakeeping ability and swiftness of sail." Over the years, many Americans have succumbed to the sweet harmonious lines and several have built their own boats to the design. Nor was it just the boating public that were drawn to this little yacht. In 1978, WoodenBoat described her as a "truly classic design (...) a real ship (...) she'd be tough as nails, easy to handle, and a joy to behold forever (...) her appeal would be universal." Six years later, she was featured again when Steve Redmond questioned her design origins: "Influenced by the Vendee boats, maybe, but based on them? Large workboats do not simply scale down into pleasing small cruisers like the Maid of Endor. Little yachts are designed, not shrunk." And there is no getting away from the fact that she is a proper little yacht-solid: "she has every structural member that a boat three times her size would have"; elegant: "one can gaze at her for hours and find nothing out of place"; usable: "she would be safe, able and great fun for one or two people who know the way of a ship."

And yet, for all these commendations nobody built a Maid of Endor in the UK. Nobody, that is, until Martin Doe met Peter Ward.

Throughout his sailing life, Martin had owned Bermudan rigged boats, from various dinghies to a Seal 22 designed by Angus Primrose. The Seal had been a favourite and Martin had sailed her for twelve years but, as his family's interest turned to horses and Martin found himself frequently without crew, he reluctantly sold her on.

Six or seven years later he had had enough of the boatless life. "I mulled it over and decided that if I was to go back afloat I was going to have a gaff rigged boat. I knew that they tended to be more cumbersome and less efficient to windward but I've always liked traditional things and besides, for years I'd been reading and re-reading John Leather's Gaff Rig."

He considered various options, amongst them the Tamarisk 24 and a twenty footer from Gaffers & Luggers but he was in no special hurry and wanted to be sure that he found the right boat for him. Then, in 1990, he stopped at Peter Ward's Wooden Boat Show stand. There, on display, was the half-model of a Maid of Endor. "I kept going back, again and again, just to look at that one model and, in the end, I asked what type of boat it was. A week or so later, Peter sent me a copy of the plans that he'd found in WoodenBoat. That was even worse ... the more I looked, the more smitten I became.

I commissioned Peter to make me a half-model like the one I'd first seen and then I started dreaming, thinking and, finally planning: how to build one and how much it would cost."

Martin was hooked. And the "experts" were full of advice: he should build it as designed, carvel. But the design was forty years old and wooden boat technology had moved on since then. How about the Hul-Tec system? Someone had built with that locally and it was an economic method for one-off building. But Maid of Endor's curves were too tight fore and aft and it would never have worked. Eventually, both for economic reasons and for ease of building, he settled on his first choice: strip plank with epoxy glass sheathing.

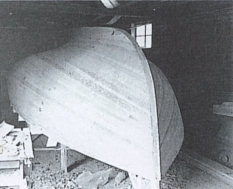

Two months later, Euan Seel started work and two months later again, the hull was ready to turn over. In that time, Euan had lofted her out full size, laminated and set up all the building frames, floors, ring-frames, stem, sternpost, and hog, fitted the bulkheads, strip-planked the hull, faired it off, applied the khaya veneer at right-angles to the strips, faired that, applied two layers of Knytex glass.

Martin found the building process one of immense excitement. "I used to go down every Saturday that Euan was in the shed. Once she was turned over, there was much to discuss: where I wanted things, what I wanted ... But before that, it was just the fascination of seeing her take shape week after week. I thought the hull a little odd initially but, of course, it's not until you've finished planking that you add the deadwood, sort out the sheer and hide the ends of the cedar strip. Then she started to look like a real boat. But there was never enough space in the shed to get a good view-it was very tight. I used to have nightmares that Euan would never manage to get her out!

"Once she was turned over the fun really started because I had to make decisions. Mostly, it was just a matter of sitting in the hull with bits of wood and working things out. Euan was very accommodating: he even sat me in the cockpit and asked me where I wanted the tiller to fall! The biggest departures from the design are the lack of foredeck hatch-I thought it would be less cluttered without-and the removal of the bridge deck. The bridge deck did allow for a larger galley but I reckoned that life would be easier without having to step over it all the time."

After the building frames were in place, the

hog and sternpost (laminated Douglas fir ) and stem and frames (laminated khaya)

were set up.

After the building frames were in place, the

hog and sternpost (laminated Douglas fir ) and stem and frames (laminated khaya)

were set up. The hull was planked in straight-edged 2" x 1/2"

cedar strip taken down to a rough sheerline.

The hull was planked in straight-edged 2" x 1/2"

cedar strip taken down to a rough sheerline. Two layers of khaya laid at 90' to the planking.

This was followed by Knytex glass cloth and Peelply was then applied (to be

removed after the resin had set) to produce a smooth finish.

Two layers of khaya laid at 90' to the planking.

This was followed by Knytex glass cloth and Peelply was then applied (to be

removed after the resin had set) to produce a smooth finish. For ease and convenience, Euan fitted most of

the plywood interior before any of the deck structure went in.

For ease and convenience, Euan fitted most of

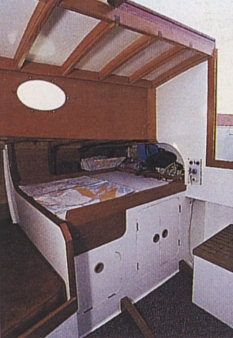

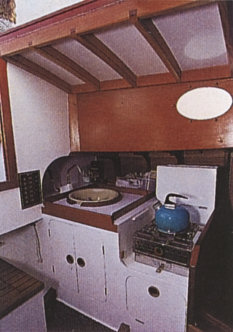

the plywood interior before any of the deck structure went in. The laminated Douglas fir deck beams were

inlaid with a 2mm strip of khaya veneer to show a dark line 1/4" above the

bottom edge. Throughout the interior the finish is a striking contrast of

lights and darks.

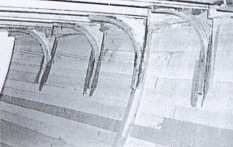

The laminated Douglas fir deck beams were

inlaid with a 2mm strip of khaya veneer to show a dark line 1/4" above the

bottom edge. Throughout the interior the finish is a striking contrast of

lights and darks. The knees (in laminated khaya with Douglas fir

chocks) were epoxy fastened and then copper riveted into the planking to give

the appearance of traditional construction.

The knees (in laminated khaya with Douglas fir

chocks) were epoxy fastened and then copper riveted into the planking to give

the appearance of traditional construction. The forward corners of the cockpit coaming were

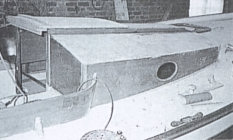

laminated separately and then joined to the side pieces.

The forward corners of the cockpit coaming were

laminated separately and then joined to the side pieces. The deck was laid prior to fitting the coachroof

sides and cockpit coaming. The coachroof was curved along its sides and across

its top.

The deck was laid prior to fitting the coachroof

sides and cockpit coaming. The coachroof was curved along its sides and across

its top. The topsides were spray-painted in Blakes' two

part polyurethane. The brightwork was finished in Epifanes varnish.

The topsides were spray-painted in Blakes' two

part polyurethane. The brightwork was finished in Epifanes varnish.

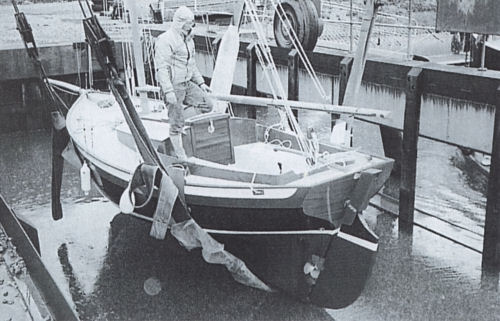

Robelia was fully rigged before launching although the sails were bent on later.

Robelia was fully rigged before launching although the sails were bent on later.

Martin took on the responsibility of sourcing most of the fittings and it became a personal obsession to obtain as much as possible from local suppliers. Being a one-off, Robelia (named for Martin's children) required one-off metal fittings, mainly in stainless steel and all bead-blasted. For the castings, Euan made up the patterns which, with the exception of the keel which was sorted out by Euan, Martin took off to be cast. At all stages there was consultation in both directions. The portlights were a perfect example. Martin and Euan both liked those drawn by John Atkin but Martin discovered that they were considerably smaller than anything available "off the shelf." So, after several attempts, they made up some patterns for rings, Martin took them off to Waterside Foundry for casting in gunmetal, ordered some toughened glass cut to shape and returned to the shed. Then it was Euan's turn: hours were spent routing out the correct shape in the solid mahogany coachroof sides to accommodate the rings and allow the glass to bed flat.

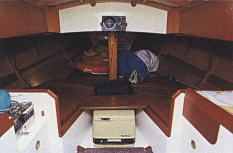

For the interior, most of the work was done before the deck was laid, indeed before even the deck beams or carlins were fitted. The galley, to port, was kept simple: a single burner, non-gimballed alcohol stove, non-draining plastic tub sink, one Whale galley faucet and a few plastic bin drawers. Opposite, to starboard a half-chart navigation table with small amount of stowage outboard and aft was fitted and the rest of the cabin was given over to twin V-berths and a Portapotti beneath a table/infill. "You can discuss and discuss, but in the end you have to make a decision. It's worked well: there isn't much space, there's only 3'10" headroom (1.2m) but it's cosy, it works and it would be fine for two people for a while."

"There's only 3' 10" headroom (1.2m) but it's

cosy and has a layout that will work well for two people for a while"

"There's only 3' 10" headroom (1.2m) but it's

cosy and has a layout that will work well for two people for a while"

By the time Robelia was launched (on a very wet day in the spring of 1992) she was complete right up to her rigging and sails. Again, Martin had called on local experts. T S Rigging and sailmaker, Arthur Taylor. The rigging is of a very high quality and maybe slightly over-substantial but, as Martin says, it's better to be safe than sorry and it certainly doesn't look wrong. He has kept everything as traditional in appearance as possible: Hempline is used for all the running rigging except the foresail sheets, the running backstays come to Tufnol blocks, the sheets lead to ash cleats. The sails, too, are beautifully made: well-cut, finely stitched and, to the amusement of both Martin and Peter Chesworth, the mainsail is enhanced by dark tan, just an inch wide, down the length of its leech: "to give the sail definition in photographs," the sailmaker ad told him, "she's bound to be photographed, that boat."

And how right he was. Since she first appeared on the mooring, Robelia has received nothing but compliments. Perhaps it's the sweet sheer, or the fine bow, or the bright-finished radiused transom, or maybe the gentle tumblehome, or the exceptionally "chunky" beam for so small a boat; Martin cannot be sure but, just as he returned time and again to the half-model, so he now finds other yachtsmen rowing round and round his mooring.

Nor has Robelia disappointed in her performance. Thanks to the beam and the ballast, she's so stiff that she barely moves when you walk around her decks and yet, when you take off in a bit of a breeze, she heels to it smoothly, just enough to dig her shoulder in and make tracks. When you look over the transom, there's barely a ripple. She points well for her rig and Martin and I gave a Twister's owner something to think about the day we tacked out of the Pyefleet-he was going faster than us but I doubt if he was getting more than a point or two closer to the wind. Still, it has to be said that Robelia has little respect for pinching, she slows right down and almost dies in the water, but, sail her free by just a few degrees, and you get smooth, purposeful motion, very slight weather helm and a commendable tracking ability...

Every so often you come across a man who is perfectly content with his choice of boat-Martin Doe is one of those men.

Every so often you come across a boat that is so classic in its design, so timeless in its line and so finely-executed in its construction that you understand instantly why it exists ... Robelia is one of those boats.

|

|

![]()

Plans for Maid of Endor are $120