![]()

Eleven days after leaving the Chagos archipelago my wife Tiffany and I, along with our two-year-old daughter Solianna, sailed towards the northern tip of Madagascar on our 34-foot sailboat Vixen. We planned to stop at the port of Diego Suarez before continuing on to the protected waters of Madagascar's west coast. Plans changed, however, at three in the morning just 20 miles from the safety of Diego Suarez. As we approached Madagascar the wind increased and shifted to the south 30, 35 and up to 40 knots. Adding to the difficulties of making our landfall, a savage four-knot current was sweeping us north. So much for Diego Suarez; now we just hoped to tuck into the lee of Cape Ambre at Madagascar's northern tip. This, too, soon proved to be a futile hope. The combination of gale force winds and unbelievable current was taking Vixen to North Africa!

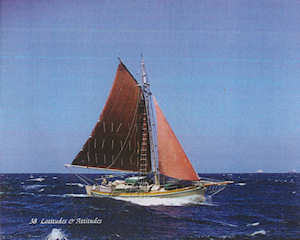

It was time to get serious. We tucked in a third reef, put up the storm jib and headed up to close-hauled. I knew it would be a test for a 57-year-old gaff-rigger to beat into these conditions. It would be a test for any boat. To my amazement Vixen went to work and little by little Madagascar grew on the horizon as our little ship fought to windward and worked her way out of the current. Early the next morning we anchored safely in the lee of Madagascar.

It was not the first time our boat had proven her mettle. In 1958 she had crossed the Indian Ocean with her first owners, Jim and Jean Stark of Miami, Florida. Although I don't know much about that first circumnavigation (the ship's papers note that Jim Stark's second wife burned all the photos and film of the journey!) there is a record of her being in Durban, South Africa on Christmas Day 1958.

I know that Jim Stark had been a bosun in the navy; I can imagine him serving in the Second World War and dreaming, as many enlisted men did, of the cruising boat he would build when the war was over. He probably read The Rudder magazine where he would have seen Atkin's articles and designs. In 1950, with a circumnavigation in mind, the Starks commissioned a design from John Atkin.

The vessel Atkin designed for the Starks was typical of his earlier work and that of his father - a double-ended, heavy-displacement, full-keeled boat in the spirit of the Norwegian designer Colin Archer. Even in 1950 the gaff-rig was anachronistic but Atkin believed in the safety of the low-aspect rig and its power when running off the wind.

Atkin wrote in Rudder magazine: "Vixen was conceived and grew into a mature, wholesome, modestly fast and able vessel, aboard which one might venture forth and return from the unknown in safety and comfort. While all manner of opinions come to mind involving just what constitutes the ideal world cruiser, it is my opinion that Vixen, considering her size and overall characteristics, comes pretty close to fulfilling most of these requirements in a highly satisfactory manner."

In 1960, having successfully completed their circumnavigation, the Starks sold Vixen. Over the next 30 years she had many different owners. She was taken through the Panama Canal for the second time, spent some time in Alaska and finally found her way into the care of Les Schnick of Port Townsend, Washington, who spent 12 years restoring Vixen from keel bolts to mast truck. When Tiffany and I saw her in 2002 at the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Show she was essentially a new boat and she was for sale. Floating at the dock Vixen looked ready to take her owners anywhere on the world's oceans. A few months later we bought her from Les. The next two years were spent living aboard in Victoria, Canada and in September of 2004 we sailed to Hawaii.

It is on the open ocean that Vixen performs best. Her heavy displacement imparts a sense of security. The bowsprit, low-aspect rig and long traditional keel keep her on course. In fact, we have no self-steering gear except for a line running from the staysail to the tiller. Perhaps Vixen's most redeeming feature is her ability to heave-to in a gale without any fuss or worry.

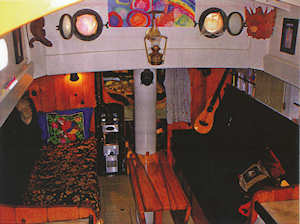

Below decks Vixen has the classic layout of a boat from the 1950s with a head to starboard, a generous amount of room for the galley, two sea berths port and starboard and a double berth in the forepeak. Being double-ended the stem has less room than a transom-ended vessel, but still offers a fair amount of storage and houses a Perkins 4-108 diesel engine for auxiliary power. Oil lamps, varnished knotty pine bulkheads and bronze ports add to the traditional feel of the interior.

Overall, Vixen is a fairly simple boat without a lot of electronics or gadgetry. One 30-watt solar panel provides plenty of electricity to run the VHF radio, interior lights and navigation lights. There are no roller-furlers or electric winches to help manage the sails and this makes Vixen a physical boat to sail. Considering we might raise anchor a hundred times a year, Vixen's Muir electric windlass is a much appreciated piece of equipment.

Aside from the highly functional aspect of Vixen and, to my eye, her beauty, there is the psychological comfort of knowing she has done it all before. She has weathered gales and wallowed in calms. She has fought her way off lee shores and romped downwind in the trades. Once, in Whangarei, New Zealand we had Vixen out of the water to put on some bottom paint. An old sea dog walked up, planted his feet squarely, pointed at Vixen and proclaimed, "I anchored next to your boat � Tahiti, 1957."

The genius of John Atkin was his ability to recognize what was essential for a safe, comfortable cruising boat and then incorporate these elements into a shape that was pleasing to the eye. Now, five years after leaving the west coast of North America and on our way to Brazil from South Africa, Vixen has proven, for the second time around, to be a fine example of Atkin's genius.

Bruce Halabisky is always happy to hear from anyone who knows more of Vixen's history or of Jim and Jean Stark of Miami, Florida. You can contact him at: brucehalabisky@hotmail.com. Plans for Vixen are available from Atkin & Co.